KNOWLEDGE AND THE KNOWER—ETHICS

Apprenticeship in ethics

Group of Jain nuns. They attach white cloths over their mouths so as to not accidentally inhale an insect. Photo: Arjunstc–Arjun

META-THINKING ABOUT ETHICS IN TOK

Ethics is one of the four elements of the TOK framework.

At this stage of their young lives, the vast majority of TOK students will have acquired a significant degree of social and political sophistication, infused with some strong ethical intuitions. That said, most students will not have explored ethical frames, formally and systematically, previously in the classroom. Many will be encountering the specific vocabulary, and associated meta-perspectives, in this unit for the first time. From the teacher viewpoint—that is an exciting prospect as well as a meaningful responsibility!

Class discussion around the various overlapping ethical frames can become quite animated especially in this current era of AI, attention-algorithm-driven social media, and existential threats.

The class activity provides a brief introduction to some of the theoretical frames that have arisen over the centuries to make sense of ethical conundrums large and small. Here is the roster:

Deontological

Consequential (Utilitarian)

Intention

Virtue Ethics

Intuition (and proximity)

Common sense

Relativism

Veil of Ignorance

Personhood (Sentience)

Technomorality

CLASS ACTIVITY—APPRENTICESHIP IN ETHICS:

INTRODUCING ETHICAL FRAMES

This class hinges on a teacher led lecture/discussion using a Google Slides presentation or equivalent. Students are seated in randomly assigned pairs. After each ethical frame is introduced, the teacher pauses so that student partners can wrestle with the generative questions (bulleted and in bold font) for a timed three minutes. After each partner conversation, students are invited to report back their findings to the entire class to stimulate lively discussion.

Echoing TOK Essay and Exhibition criteria—encourage students in advance to anchor their theoretical ethical notions in everyday, real-life examples.

INTRODUCTION

That night the soup tasted of corpses (2024) Oil painting by the author inspired by Elie Wiesel's book Night.

No single theoretical approach to a complex ethical scenario seems to suffice. When tackling a conundrum in the ethical realm, it is worth unpacking the situation utilizing several of the—inherently overlapping—conceptual frameworks that we will explore today.

1. DEONTOLOGICAL 👁

Obeying rules. Involves obligation and duty.

In the Ethics vs. Morality session the class made personal lists of rules to live by. “Keep your promises,” “Don’t kill,” and “Avoid eating human flesh” were included in the prompt. Here is a snapshot sample of some of our student-generated obligations and taboos:

Obey the Rule of Law

Don't lie

Pay Parking tickets

Don't marry your brother or sister

Eat kosher or halal

Can you identify the seven religious traditions represented by the symbols in this graphic? Is it fair to conclude that they are essentially asserting the same thing?

A. Golden Rule

The Golden Rule is treating others as you would like them to treat you. Variations on this ethic of reciprocity emerged in the tenets of prominent religions and creeds stretching back to the very beginnings of recorded history.

Can you think of an application of the Golden Rule from your own life experience? To what extent does a version of the Golden Rule work for you?

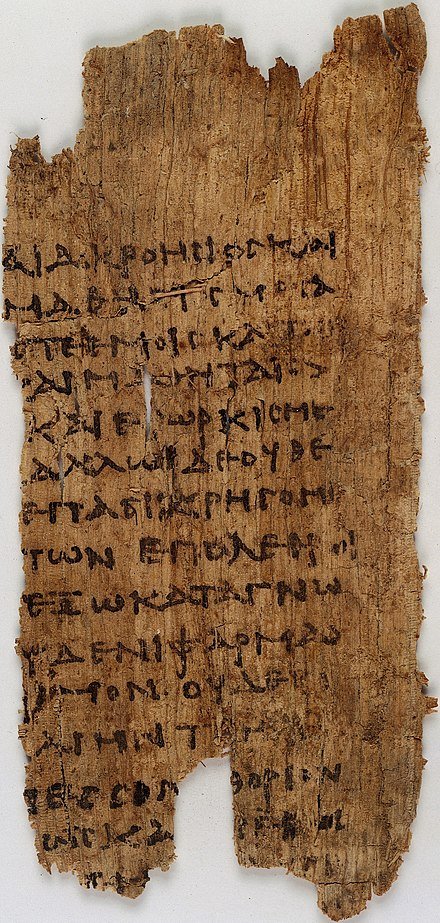

Fragment of the Hippocratic oath on the Papyrus Oxyrhynchus (2547 AD).

An engraving portraying the ancient Greek physician known as Hippocrates (460–370 BC) rendered by Dutch master Peter Paul Rubens in 1638.

B. Hippocratic Oath

A version of the Hippocratic Oath has been sworn by qualifying physicians for centuries. The iconic phrase "First do no harm" (Primum non nocere in Latin) encapsulates the spirit of the ancient texts, but likely dates from the 17th century.

To what extent is "First do no harm" a worthy, universal rule to live by?

Based on your knowledge of medical practice, historically and/or in the present moment, provide real-life examples where the of application of Hippocratic Oath has broken down or seems questionable?

C. Kant's Categorical Imperative

"Act only according to that maxim whereby you can, at the same time,

will that it should become a Universal Law"

1790 portrait of German enlightenment philosopher, Immanuel Kant by an unknown artist.

Kant is quite strict. A Categorical Imperative is an inescapable, rational, unconditional requirement that must be obeyed in all circumstances and all times.

To what extent do the Golden Rule and the Hippocratic Oath hold up as categorical imperatives?

Based on your own life experience, has “never lie” worked for you as a categorical imperative? Explain your response with reference to a specific scenario.

Kill one to save five, or do nothing at all?

2. CONSEQUENTIAL (UTILITARIAN) 👁

Consequences. Discerning resulting benefits or harm.

The technical terms “utilitarian” and “deontological” appear alienating at first encounter, but they are fundamental concepts, fully embedded into our cultural heritage. As soon as their meanings are revealed, students immediately realize that they already understand them. Since most will engage with this philosophical terminology soon enough, in their undergraduate studies, they are introduced here in TOK without apology.

In getting to grips with an ethical situation the outcome—what actually happened as the result of actions taken—is the undeniable, objective bottom line. That said, what else should be taken into consideration when judging a real-life ethical scenario?

Utilitarianism emerges naturally from consequentialism. Utilitarianism aims for the "greatest good (or happiness) for the greatest number." This appears seductive; but it can sometimes entail dire consequences for individual victims. Happiness, especially in an entire population, and considering future generations is not easy to measure!

The immense challenge—or outright folly—of attempting a “calculus of felicity” is further explored in Why is ethics like math and not like math? Sacrificing a single individual to save many is, of course, the underlying theme of text book Trolley problems.

Image credit: Scrofano Law D.C.

3. INTENTION 👁

In apportioning blame or responsibility, intentions come into play; but there are complications. There is a difference between unlucky, unforeseen consequences and negative outcomes that the result of irresponsible choices that entail a high chance of perfectly foreseeable bad consequences. And it also works the other way—if it is your general inclination or personality disposition to do the right thing; without dilemma or moral struggle, can you give yourself any credit for having made an ethical decision?

How might a judge take into account a guilty defendant’s intention when sentencing in a court of law?

Can pure altruism exist? Be specific—justify your response with real-life rather than hypothetical examples.

When did you last say “But, I didn’t mean it”?

Aristotle arguing with his mentor Plato. It is not going well. Aristotle asserts, in his Nicomachean Ethics, that “There cannot be a universal good such as Plato held to be the culmination of his Theory of Forms.”

Luca della Robbia (1437) Marble panel. Museo dell'Opera del Duomo. Florence, Italy

4. VIRTUE ETHICS 👁

Developing positive character traits such as honesty, compassion and generosity.

A. What is the good life?

The ancient Greek philosopher, Aristotle had a compelling take on this with his "Golden Mean." For example: the virtue of Courage lies between vices of Fear and Recklessness. Aristotle famously took a big picture, down-to-earth, lifelong approach; emphasizing the steady accumulation of virtuous habits—what you do everyday is what you become!

“[T]he good for man is an activity of the soul in accordance with virtue… There is a further qualification: in a complete lifetime. One swallow does not make a summer; neither does one day, or a brief space of time, make a man blessed and happy.”

Aristotle did not have a monopoly on virtue ethics. Whether we recognize them “persistent memes” or “useful fictions,” virtue ethic iterations in other cultural traditions, extending back to ancient times in different geographical locations, have prevailed. They have evolved. They have driven ritual practice and cultural attitudes, globally.

Eightfold Path of the Buddha on the Wheel of Dharma.

Image credit: Buddhist Weekly

Confucius—5 Virtues

Image credit: Sharyl Wells

Variations on the 5 Virtues of Confucius and the Buddhist Eightfold path are central examples. There are many more. The various traditions have family resemblances with regard to each other, but have different emphases. For example, both the Confucian and Buddhist traditions seem less individualistic, and embrace a larger timescale than Aristotle. They are here for the long game! Confucianism places particular emphasis on “humanity,” and honoring family and ancestry. The Buddhist tradition deemphasizes the self and underscores a deeper connection to the entire cosmos.

Aristotelian, Confucian and Buddhist virtue traditions are only part of a fascinating, interwoven, pluralistic, global tapestry. The list is long. Consider traditional Islamic and Nordic attitudes to honor and hospitality, the centrality of “community” in Judaism, and Arjuna wrestling with fate and duty in the sacred Hindu text, Bhagavad Gita.

What is missing here? What key virtues in cultural traditions not mentioned here come to mind?

Aristotle’s writings were not kind to slaves or women, to what extent does this negate his legitimacy?

Just whimsically checking here—can you differentiate between the Golden Mean and the Golden Rule?

Multifarious global traditions and rituals are further explored in the Knowledge and Indigenous Societies and Knowledge and Religion optional themes.

B. Human flourishing

What the virtue traditions have in common is the habitual development of multiple virtues in the pursuit of good living. This begins with the individual but is also embedded in kinship and politics. The development of real-world prudence and practical wisdom in the context of an entire lifetime is the goal—not idealized perfection!

This all boils down to the notion of human flourishing. Human flourishing is not mere survival. It implies freedom from constraints that deny the fulfillment of human potential; not just for the individual, but for humanity as a whole and for future generations!

“A Robin Red breast in a Cage

Puts all Heaven in a Rage ”

AI generated

Explain the poetic metaphor of the caged bird in the context of human flourishing.

To what extent does “act in order to enhance overall human flourishing” work as a bottom-line categorical imperative?

“Until we are all free, we are none of us free.”

Ethical cartoon echoing Blake’s “Robin redbreast in a cage.”

Image credit: Mara Lea Brown

TOK students may have previously worked with kindergarten-aged students to interpret ethical cartoons, including this sad cat confined in a cramped cage, in the What do little kids know? class activity. The sense of outrage we feel when human potential is stultified, was the main theme in the “Truman Show—on the air unaware,” the second class activity in the Allegory of the Cave unit.

If the notion of human flourishing encompasses humanity as a whole including future generations what are the implications for the ethics of addressing climate change?

To what extent must virtue ethics extend to other sentient beings?

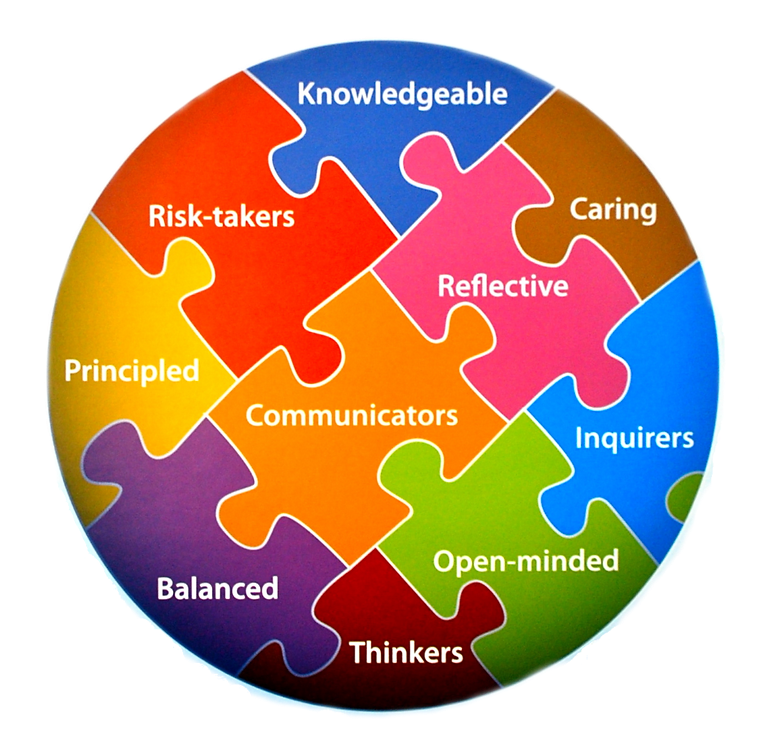

IB PROFILE INTERLUDE

Here is the IB Learner Profile.

To what extent do the IB Learner attributes work like virtue ethics?

Are these attributes real? Do they resonate with you as you navigate your own IB Diploma journey?

Who do you think formulated the IB profile, and what was the likely motivation?

5. INTUITION (AND PROXIMITY) 👁

Often an ethical action is best explained by the upwelling of a personal feeling that can appear in the moment and may defy rationality or formal explanation.

Our moral intuitions are also influenced by proximity.

Are we fundamentally tribal?

Do we instinctively treat family and close friends more kindly than strangers?

And how does physical distance come into play? An in-your-face scenario is different from an abstract case.

To what extent is social distance necessary for objectivity in making ethical judgments.

Elsewhere on the site, the Trolley problems unit explores intuition and critical distance in greater depth; and Asch and Milgram experiments add a further social, peer pressure twist. Why is ethics like math and not like math? plays with the hubristic perils of attempting a calculus of felicity; confusing the Golden mean with the arithmetic mean; and the tantalizing notion of—wait for it—a self-evident, intuitive, axiomatic foundation for all of ethics!

6. COMMON SENSE 👁

In the end do ethical decisions boil down to good old common sense?

You decide. Just use your common sense.

Image credit: Thomas Valenti at Medium

7. RELATIVISM 👁

The same action may be right in one cultural setting and very wrong in another.

The Exorcising cultural relativism unit is placed in the Knowledge and Indigenous Societies optional theme.

8. VEIL OF IGNORANCE 👁

A thought experiment that can serve justice.

Blind Justice: Bronze reproduction after French sculptor Nicolas Mayer (1852-1929)

Imagine that you have set for yourself the task of developing a totally new social contract for today's society. How could you do so fairly? Although you could never actually eliminate all of your personal biases and prejudices, you would need to take steps at least to minimize them. Rawls suggests that you imagine yourself in an original position behind a Veil of Ignorance.

Behind this veil, you know nothing of yourself and your natural abilities, or your position in society. You know nothing of your sex, race, nationality, or individual tastes. The Veil of Ignorance is explored in greater detail in the Epistemic justice unit in the Human Sciences Area of Knowledge.

9. PERSONHOOD (SENTIENCE) 👁👁

Wistful juvenile orangutan

Image credit: World Animal Protection, Canada

Persons are conscious and they can suffer. Persons have agency and autonomy. Personhood plays into notions like liberty and equality. Personhood comes with rights and responsibilities.

We concluded the Virtue Ethics section by asking “To what extent must virtue ethics extend to other sentient beings?” The ethics of personhood, instrumentality and flourishing is a critical factor in Sentience continuum and Octopus intelligence (in the Knowledge and the Knower core theme), and is further consolidated in Gorillas, robots and personhood (in the Knowledge and technology optional theme).

10. TECHNOMORALITY 👁

Technomorality is the existential elephant in this room. Technology—from stone tools to AI—has always augmented our embodied and culturally embedded, smart ape phenotype. Technology is inextricable from the ethical frameworks outlined in this brief introduction. Visit the Technomorality unit in the Knowledge and Technology optional theme.

ACKnowledgement

Edinburgh University philosopher of technology Shannon Vallor champions “Technomorality” in Technology and the Virtues: A Philosophical Guide to a Future Worth Wanting (2016). Professor Vallor’s thinking, together with Alasdair Macintyre’s After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory (1981), influenced the Virtue Ethics portion of this introductory lecture/discussion on ethics.

WHAT TO DO NEXT?

CONCLUDING ETHICS CLASSES

IN THE KNOWLEDGE AND THE KNOWER CORE THEME

Saint or serial killer? is provided as an in-depth, ethical case study. We get to know the characters involved, must search for the significant facts, and navigate cultural context. The class culminates in an in-depth writing assignment that builds TOK Essay and Exhibition skills.

Seven Deadly Sins is on the lighter side. It serves as an informal, upbeat way to “conclude” the Ethics element in the Knowledge and the Knower core theme. Spoiler alert: students will gain a new understanding of what it means to be “vicious”!

Finally, for any educators (and/or students) motivated to acquire a deeper understanding of some of the more nuanced technicalities of ethical nomenclature, a brief visit to deontological demystified is recommended.

Norman Rockwell (1961) Golden Rule. Oil on Canvas. Norman Rockwell Museum, MA.