KNOWLEDGE AND THE KNOWER—TOOLS

INTUITION

Intuitions are a vivid aspect of our subjective experience. We often use the term ‘intuition’ as a catch-all label for a variety of effortless, inescapable, self-evident perceptions or flashes of insight that seem to arrive fully-formed and without warning.

Intuitions are hard to define and difficult to talk about with precision. Their origins and mechanisms are hidden and murky. They are the product of physiological and neural processes well below the level of conscious awareness or any reasoned discernment.

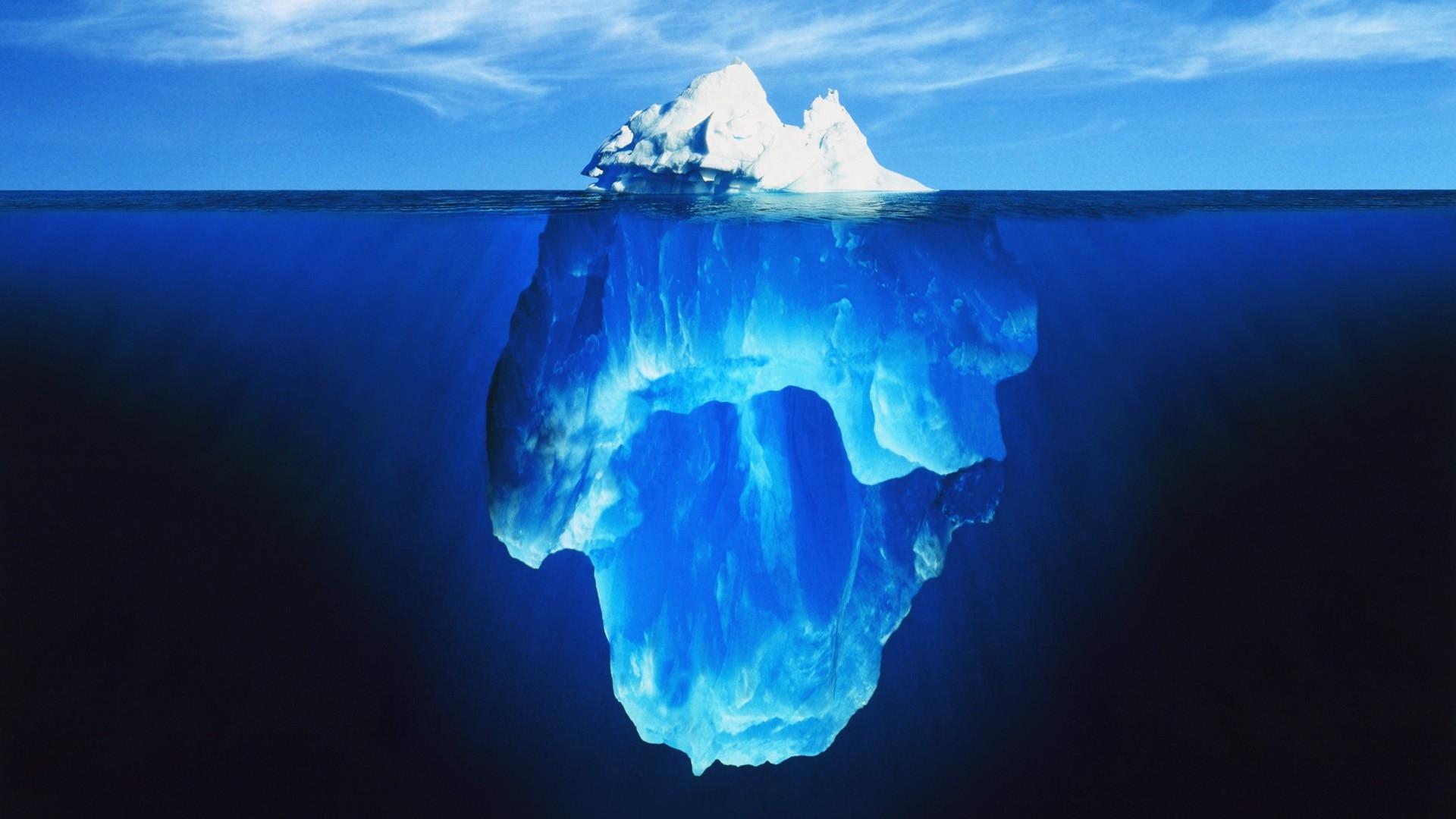

It seems that the explicit conscious thoughts that we can articulate are just the tip of our cognitive iceberg. The subconscious mind, introduced by Freud with great literary aplomb, and still in the very early stages of exploration by neuroscience, remains mysterious and enigmatic.

Intuition allows us make judgments in the blink of an eye without careful deliberation or systematic analysis of all the available facts. We trust our “gut” reactions and first impressions. They enable us to discern the sincerity of a conversation partner, read the prevailing ambience in a room or feel a sense of impending doom. These insights or early warning "survival" mechanisms are palpable and we ignore them at our peril. They are only irrational in the sense that the cognitive fragments (some of them non-linguistic) and experiential memories that support them remain largely hidden.

CLASS ACTIVITY—ESTIMATE 3 MINUTES

Ask two volunteer students to act as assistants. Tell the remainder of the class that they are about to enter a zone of sensory distortion and introspection; and must listen to the instructions carefully. Ask one of the student volunteers to read out the instructions slowly and "mindfully":

1. Close your eyes... Relax completely... Focus your own gentle breathing... Notice the sounds around you, but do not be distracted by them...

2. In a moment, when a I say "begin," keep your eyes closed and try to estimate when three minutes have passed. At that point simply raise your hand. My assistant will touch your hand gently to indicate that the number of seconds of your estimate has been logged and that you can lower your hand. After that you will continue to keep your eyes closed, and continue to relax, until I say, "now open your eyes." to indicate that the activity has ended.

The times (in seconds) and student first names can be recorded in sequence by an assistant on the whiteboard. The assistants should ask the following generative questions to get some initial class discussion going.

What happened?

What was going on?

Be honest did you count?

Was this fast (intuitive) or slow (analytical) thinking?

Before moving to the “Don’t think… act?” class activity below, allow the whole class to take a first pass at addressing the following Knowledge Questions. Intuition is perhaps the most inchoate and enigmatic aspect of how we know.

LOOMING KNOWLEDGE QUESTIONS

How much of intuition can be attributed to genetically-determined, "hard wired" instinct?

Can intuition be honed? What is the relationship between learning and intuition? Does the trained musician, dancer or mathematician have richer insights than untrained individuals in their respective fields?

Is intuition the mysterious stuff of creativity?

Mathematical proof hinges on hard logic and an assumption of certainty, but the axioms of mathematics are taken as self-evident. Is the edifice of mathematics founded on a fragile base of intuition?

When we make complex judgments in context are we relying mostly on intuition? Is there a genetically determined ethical instinct?

Another smart ape that relies on instincts/intuition... a young Bonobo from the Congo Basin

CLASS ACTIVITY II—DON’T THINk… ACT!

Initially arrange students in random groups of four. Tell them that the goal of the activity is to think back to a time when they used their powers of intuition, then share the story with the other members of the group. The team members may help bring out the full story by asking probing clarification questions. After five timed minutes of group conversation, interrupt the proceedings and ask how many students have a coherent story to share. Call on two or three volunteers to tell their stories to the whole group.

Some students will find this task difficult and will not be able to recall or pinpoint a relevant incident.

Next, rearrange students to make groups of six. Provide all students with a copy of the bullet points below as extra stimulus material. Spell out that the bullet points cover one dozen generic aspects of intuition. The student task is to identify one that resonates with their own life experience and, just like before, generate a personal story. As so often in TOK, the students will be appropriating a general idea and backing it up with a specific real-life example. Allow a full seven minutes this time.

Printable pdf. of the bullet points.

ONE DOZEN ASPECTS OF INTUITIVE, FAST THINKING

You made a snap decision without using any intellectual analysis

You trusted your gut in a tough or awkward situation

You used your instincts or physical reflexes in a potentially life or death scenario

You had a feeling about entering a place or situation that you could not define that something was not quite right

You trusted your intuition at the time but it turned out that you misread the situation and got it all wrong

You felt tired and down but you put in one of your best performances

You used your intuition effectively in a creative or problem-solving situation

You overcome stage fright or otherwise used nervous energy in a positive way

You experienced a palpable feeling of déjà vu

You instantly stereotyped somebody

You did the opposite of following all the sensible advice and arguments and followed your own feelings

You performed very well in a physical skill because all the long hours of training and practice, as well as your natural talent

When the time is up, allow the students a short break and rearrange the chairs in an intimate circle.

Invite students to relate their stories in rapid fire. Get the activity rolling by calling on an individual volunteer. Inform them that, moving forward, the protocol will be that the person ending their story nominates the next person to take their turn. If time permits: try to hear every voice. Let spontaneous guided discussion ensue.

Leopard confronts a baboon, Botswana

Photo: John Dominis for Time/Life (1966)