KNOWLEDGE AND THE KNOWER—PERSPECTIVES

INTERPRETATION—WHAT’s HAppening?

Guest conductor Joseph Young leading the Berkeley Symphony orchestra.

Photo credit: Dr. David S. Weiland

Interpretation is enormously important… and it’s happening right now! Interpretation is not just a worthy TOK Concept. It feels much more like a verb than a noun, and it undergirds much of what it is to be a knowing, thinking, curious, sentient human.

Interpretation has a flavor of its own, but it is by no means a standalone aspect of how we know. It blurs—and has family resemblances—with other behemoth knowledge meta-ideas like explanation, perspective and perception.

Rather than philosophizing tangentially about Interpretation, or getting bogged down in definitions and etymology, we will take a “Look, don't overthink!” approach. The hands-on class activities and provocative generative questions that follow, will enable collaborative groups of students to jump-out-of-their-boxes, and to explore what it is like to interpret—intentionally, reflectively and multifariously.

This unit extends over several class periods. It could also be adapted as an engaging day-long workshop, a TOK demo-class for parents or faculty, or as a set-piece for an overnight TOK Retreat.

OVERVIEW

An evocative and pertinent soul music track is played as students enter class. This is followed by a familiar warm-up activity.

There are a total of eight contrasting, hands-on activities. The first three activities (I, II and III) run consecutively with all four student groups participating. Students explore Knowledge Questions and dive into a full-class discussion only when all three activities have been completed.

Next, each student group is assigned one of the four remaining activities (IV, V, VI and VII). These are tackled simultaneously. When the dust clears, students adopt a constructivist pedagogical role—sharing their group findings and posing Knowledge Questions to the entire class.

Finally, in activity VIII, students are challenged to consider what Interpretation implies for a lifetime of learning!

WHAT’s Going on?

Arrive to class early and have Marvin Gaye’s classic 1971 What’s happening, brother? playing as students enter the class. Fade the music and start the class without further comment. As always in TOK: familiarity and strangeness will be the order of the day!

60 SECOND WARM-UP:

Ready, fire… Aim!

Invite a fearless student “volunteer” to speak for just a minute without hesitation, repetition or deviation. (Follow the link for a fuller description of this engaging class ritual.) Today’s given subject is (you guessed it)—”Interpretation.”

This how you say “interpreter” in American Sign language (ASL). Photo credit: Timothy Revell, Getty image.

three INTRODUCTORY activities

Acknowledge the “Just a minute” student winner. Resist the temptation to plunge into deep discussion immediately Nevertheless, do make a point of highlighting some specific aspects of “Interpretation” that emerged in the 60 seconds. Also simply draw attention to, rather than actually discuss, the orchestral conductor and sign language images to further set the scene.

Then speedily divide the class into the four groups. Tell them that they will stay together for the first three activities. The game is on!

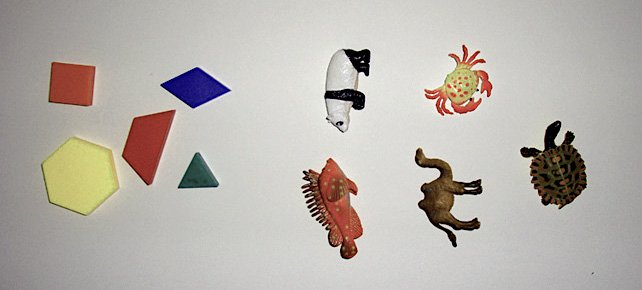

CLASS ACTIVITY I: IDENTIFYING GEOMETRIC SHAPES AND PLASTIC ANIMALS BY TOUCH ALONE

Students should read the following instructions before undertaking the experiment.

While partner A’s back is turned, partner B collects the 5 geometric shapes and selects 5 different plastic animals. Partner A, with back still turned away, puts out a hand. Partner B performs the following tests with each shape or animal in turn.

Without moving the object at all, press it gently into Partner A’s fingertips and hold it still for a five second count.

Allow partner A to hold the plastic animal and move it around at will in the hand for a full five second count.

Partner A must try to guess the object at each stage . Don’t be too strict: a guess of “monkey” for a Lowland Gorilla is perfectly satisfactory. Record your results in the table below. Also record “Don’t knows” and wrong guesses.

Full-sized tables in a Google Doc

““Our sense perceptions are already the result of this assimilation and equalization with regard to all the past in us...”

Hold off on questions and comments for now. Designate a student to read aloud the Nietzsche quote above, and have fun with the 11 second Muppet video below. Move on briskly to Class Activity II.

CLASS ACTIVITY II:

DISCERN THE RULES OF INVENTED GAMES

The following activity also appears in Language games, as part of the Knowledge and Language optional theme. The emphasis here is on discerning the rules, live and in the moment, of previously unseen games.

Students are divided into four large groups and completely separated. One group can stay in the classroom. The others should, at the very least, be distanced along a long corridor, or out-of-earshot around a corner. Each group receives a novel combination of equipment. The exact selections of equipment are unimportant. Grab whatever is convenient.

GROUP 1

Deck of cards

Sets of colored plastic bears in three colors

Large plastic creature (like a whale)

Some chocolates

GROUP 2

A ball

Two different hats

Some stuffed animals

A bicycle pump

GROUP 3

Short length of rope

Blindfold

Bell

Stick

GROUP 4

Exactly as for GROUP 1

Students are given 15 minutes to invent, play, refine, name and rehearse an original game. They have only three constraints:

All equipment must be used.

There must be a winner.

The game must be safe.

The groups will be required to demonstrate their game without explanation to the remainder of the TOK class; who will attempt to discern the rules on the spot. During the activity the teacher should circulate around the various locations. Teams should be given fair warning before being told to finish the task and return to the TOK classroom for the public viewings.

As before hold off on questions and comments for now. Show the Feynman “Rules of Chess” video, let it resonate, then move on briskly to Class Activity III.

CLASS ACTIVITY III:

Interpreting texts

In this activity the four student groups are provided with the same seven texts. Inform students that their task is to peruse the texts and then arrange them in order of clarity placing the most obscure last, and the most accessible first.

Link to Google Doc of 7 texts

TEXT ONE

Hark!

Tolv two elf kater ten (it can’t be) sax.

Hork!

Pedwar pemp foify tray (it must be) twelve.

And low stole o’er the stillness the heartbeats of sleep.

White fogbow spans. The arch embattled. Mark as capsules. The nose of the man who was nought like the nasoes. It is self tinted, wrinkling, ruddled. His kep is a gorsecone. He am Gascon Titubante of Tegmine — sub — Fagi whose fixtures are mobiling so wobiling befear my remembrandts. She, exhibit next, his Anastashie. She has prayings in lowdelph. Zeehere green egg-brooms. What named blautoothdmand is yon who stares? Gu — gurtha! Gugurtha! He has becco of wild hindigan. Ho, he hath hornhide! And hvis now is for you. Pens‚e! The most beautiful of woman of the veilch veilchen veilde. She would kidds to my voult of my palace, with obscidian luppas, her aal in her dhove’s suckling. Apagemonite! Come not nere! Black! Switch out!

James Joyce (1939) Finnegan’s Wake. Beginning of Chapter 3

TEXT TWO

For her own person,

It beggared all description: She did lie

In her pavilion—cloth-of-gold, of tissue—

O’er picturing that Venus where we see

The fancy outwork nature…

...Antony,

Enthroned i’th’market-place, did sit alone,

Whistling to th’air, which, but for vacancy

Had gone to gaze on Cleopatra too,

And make a gap in nature...

Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale

Her infinite variety. Other women cloy

The appetites they feed, but she makes hungry

Where most she satisfies; for vilest things

Become themselves in her, and the holy priests

Bless her when she is riggish.

William Shakespeare (1623) Antony and Cleopatra: Act II. Scene II. First performed in 1607.

TEXT THREE

And the woman said unto the serpent, We may eat of the fruit of the trees of the garden: But of the fruit of the tree which is in the midst of the garden, God hath said, Ye shall not eat of it, neither shall ye touch it, lest ye die. And the serpent said unto the woman, Ye shall not surely die: For God doth know that in the day ye eat thereof, then your eyes shall be opened, and ye shall be as gods, knowing good and evil.

King James Bible: Chapter 3, Verses 2-7

TEXT FOUR

No doubt you know that Galileo had been convicted not long ago by the Inquisition, and that his opinion on the movement of the Earth had been condemned as heresy. Now I will tell you that all things I explain in my treatise, among which is also that same opinion about the movement of the Earth, all depend on one another, and are based upon certain evident truths. Nevertheless, I will not for the world stand up against the authority of the Church.

René Descartes (1634) Letter to Marin Mersenne

TEXT FIVE

The existential-ontological constitution of Dasein’s totality is grounded in temporality . . . How is this mode of the temporalizing of temporality (Zeitigungsmodus der Zeitlichkeit) to be interpreted? Is there a way which leads from primordial time to the meaning of being? Does time itself manifest itself as the horizon of being? (SZ: 437)

Martin Heidegger (1927: 437) Being and Time (Sein und Zeit in German) Translated by J. Macquarrie and E. Robinson

TEXT SIX

The sun did not shine.

It was too wet to play.

So we sat in the house

All that cold, cold, wet day.

I sat there with Sally.

We sat there, we two.

And I said, 'How I wish

We had something to do!'

Too wet to go out

And too cold to play ball.

So we sat in the house.

We did nothing at all.

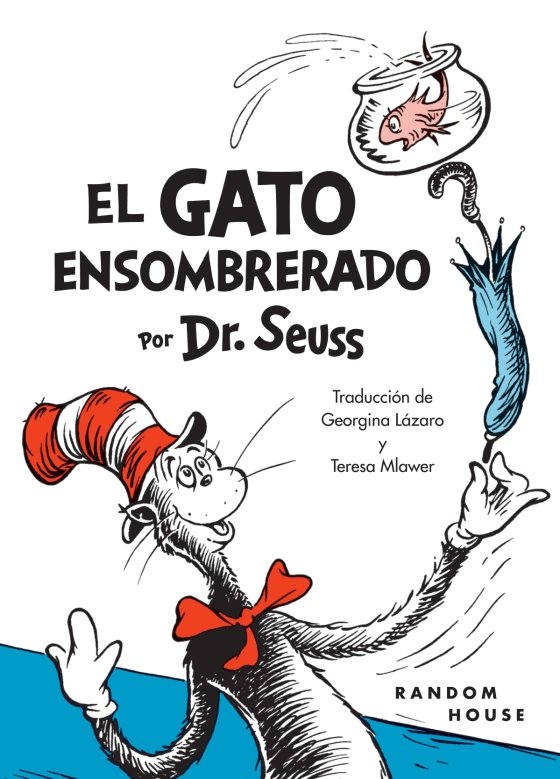

Dr. Seuss (1957: 1) The Cat in the Hat. Random House, NY.

TEXT SEVEN

Lung cryosections from K – rasV12 mice stained for senescence-associated β -galactosidase gave an instant signal in the adenomas, whereas the adenocarcinomas gave a weak or negative signal (Fig. 1b).

Nature Vol 436: 4, August 2005

GENERATIVE QUESTIONS

Now, as a whole class, tackle the following:

Think back to the introductory “Just a minute” session—what happened? What aspects of interpretation in everyday life and academia spontaneously emerged?

When identifying objects by touch alone, explain the difference between having an inert geometric shape or plastic animal pressed into your hand and being able to freely explore it?

Some geometric shapes or plastic animals were easier to interpret than others; to what extent did individual life experience play into the accuracy of response? Provide examples.

What were some of the commonalities, and some of the differences between your own subjective experience of discerning the rules of previously unseen games, as they played out in front of you, and identifying shapes by touch?

Is the study of physics interpretation?

How did you decide which texts had greater or lesser clarity than others? Is “clarity” the real issue here, or were some texts too specialized or technical? Relish elucidating your responses with some specific examples.

And just to lighten things up :

Is El gato ensomberado a good translation for Dr Seuss’s The cat in the hat? If not, why not?

Waxwork effigy of Sigmund Freud, with an bemused visitor sitting on the psychoanalysts couch, at the Madame Tussauds museum in Berlin.

Freud famously wrote in his 1900 book The Interpretation of Dreams, “The interpretation of dreams is the royal road to a knowledge of the unconscious activities of the mind.”

ACTIVITIES IV, V, VI and VII —

EACH group HAS A DESIGNATED ACTIVITY

Use the same four group configurations. The first group will attempt activity IV, the second—activity V, the third—activity VI, and the last—activity VII. Groups work simultaneously.

Students will present their findings to the entire class after a timed 12 minutes, referring to any generative questions provided in bold font. In teacher mode, presenters may choose to ask the whole class any of the prescribed questions directly and/or formulate a few of their own.

Activity IV entails an surprise imposition on the presenting group!

CLASS ACTIVITY IV—

WAys OF Putting A SPELL ON YOU

As a group listen to 10-15 second bursts of the four versions of the “I put a spell on you.” Each individual student should decide which version of song resonates with them the most and why. Also comment positively or negatively on some of the other interpretations.

Next, just for fun, step outside the classroom and briefly rehearse a Karaoke version of “I put a spell on you,” using the link. Feel free to add interpretive hand gestures or dance elements. Later you will perform this in front of the entire class!

CLASS ACTIVITY V—KUKeRI NOT KARAOKE

Image credit: Doc Weekly

What on earth is going on here? Working solo—without looking at the video below—write on a scrap of paper your initial interpretation of this image.

Next watch the New York Times video below.

How close to real-life cultural reality was your own initial interpretation of the photo of four enigmatic figures?

After engaging with the video, why do you think this cultural practice has persisted over many generations?

Briefly reflect on collective ritual or rituals that you have experienced personally?

CLASS ACTIVITY VI—MATH AND MUSIC

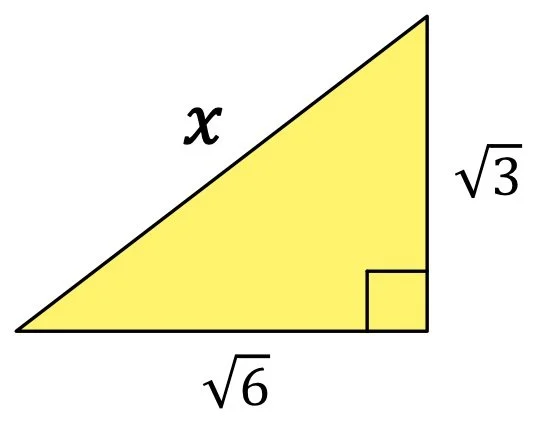

Start by working solo. Without using a calculator or pen and paper, calculate the length of the hypotenuse in the triangle below, in centimeters to one decimal place.

Next, as a group examine the this Mozart sheet music fragment. Collaborate on pointing to, and explaining, what the various formal notations mean.

Fragment of the sheet music for the Piano Sonata in A major No. 11 by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1783)

How different were individual responses in the group?

Did anyone in the group demonstrate expertise in either scenario?

To what extent did previous learning moments play into the accuracy of responses?

Music has been described as “quasi-mathematical.” Do you agree? What else is it? Justify your responses with some specific examples.

CLASS ACTIVITY VII—

What’S HAPPENING, BANKSY?

A.

B.

C.

D.

As a group examine these four Banksy artworks and answer the following:

What’s going on here? What are you seeing?

What is the essential difference between encountering pop-up Banksy street art in person, and seeing them online as digital images?

Banksy is one of the most famous artists in the world, but many folks walk past his stenciled graffiti work on walls without noticing—why?

After students have finished presented their findings for activities IV-VII to the entire class, and some lively discussion has ensued, the class will be primed for some intriguing meta-thinking in “Oneself as a Learner,” the final session.

Oneself as a Learner

By this juncture, it is a glaring truism that “Interpretation” is an enormous TOK Concept that touches on much of what it means to be human. It hides in plain sight. In the seven group activities, and in the discussions that followed, we experienced and reflected upon Interpretation in multifarious contexts including:

Performing music written down formally on a musical score.

Translating between languages

Understanding texts of varying levels of complexity

Discovering personal meaning in works of art

Hypothesizing explanations in science

Figuring out how to tackle a math problem

Noticing that sense perception is dynamic and active, rather than passive.

Attempting to comprehend a ritual practice from another culture

Trying to make sense of a strange dream

Anything missing? What else should we add to this list?

Bollywood dancers

Image credit: EA Corporate Entertainment Agency

Breaking the 4th wall for TOK teacher facilitators

When we find ourselves improvising on stage, unpacking a movie plot, experiencing our first kiss, deconstructing a political treatise, navigating bereavement, analyzing lab data, or cracking up at slapstick TikTok, we are, most certainly—in the thick of the action—interpreting!

Interpretation is omnipresent because of our insatiable curiosity. This is sometimes referred to as “epistemic hunger.” We notice, assimilate, and try to make sense of the novel, unexpected or problematic things that appear before us. Our attention is engaged. We ask ourselves, inwardly,“What on earth is going on here?”

Both in the prison of our own subjectivity and collectively; we mentally rearrange, and reframe, the new things we encounter to render them accessible—to make them fit, make them our own! We learn and adapt as we go—constructing useful fictions—large and small, capable and fallible—that, at least for the interim, appear fit for purpose, and cohere with our (co-authored) life stories.

Class activity VII—

PIVOTAL learning experiences

Cabbage moth pupa in soil.

Photo credit: Wildlife Insight

Launch the class with a public reading of the following true story by Andrew Brown, author of the TOKResource website. Even better—from a teacher authenticity/trust perspective—set the frame by preparing the narrative of a vivid learning experience of your own! If you decide to go with “Shiny Brown Pupa,” be sure to share your own learning experience during the subsequent class “show-and-tell” session.

SHINY BROWN PUPA—

A PIVOTAL LEARNING EXPERIENCE

As a small child I remember digging up and cutting open a shiny brown pupa. I wanted to discover the secret of metamorphosis. I had hoped to examine a living creature inside that would be part caterpillar, and part large butterfly. The model that I had constructed for myself to explain the transition was based partly on commonsense; and partly on the crude special effects seen in old black and white horror movies. At the climactic moment, Wolfman sprouts fur, claws and fangs in the glare of the full moon. In this model the transition is always complete. It happens gradually, before our very eyes.

As soon as I cut into the pupa—a runny, off-white "soup" trickled down my hand. I was left with only an empty, sculpted husk. I had killed the fragile creature within. I was guilt-ridden and astonished, but not in any positive sense.

All my preconceptions were shattered and I was at an impasse. Asking others for an explanation or doing some research would have been out of the question. I knew more natural history than the adults around me, including my parents or elementary school teacher. The superficial coverage in my "age-appropriate" books was no more helpful. Illustrations and the descriptive, epithet "complete metamorphosis" were no substitute for a proper explanation. All of my questions remained. Where had the caterpillar gone? How could something as complicated and spectacular as a butterfly emerge from an amorphous, gooey mess? I was never to repeat the murderous experiment. I remember my feelings at the time quite vividly. I felt crushed and bewildered. I had experienced directly the powerlessness and alienation of living in a world that I could not quite understand.

Decades later, as a trained zoologist and teacher, I can open an undergraduate text (Curtis and Barnes, 1989) to read:

During the outwardly lifeless stage most of the larval cells break down, and entirely new groups of cells, set aside in the embryo, begin to proliferate using the degenerating larval tissue as a culture medium. These groups of cells develop into the more complicated structures of the adult.

I still get a thrill when I think about this and never get tired of reading about it in scientific journals. To think that ontogeny (the unrolling of the genetic code as the embryo develops) occurs twice—the second time: only slightly less from scratch than the first! The purpose of the caterpillar—an "eating machine" supreme—is, precisely, to convert as many green leaves as possible to its large, worm-like body. The caterpillar (with the exception of a few patches of cells destined to grow into the adult butterfly) self-destructs on hormonal cue and, as an amorphous, nutrient soup, provides the necessary food and raw material for constructing the butterfly—a short-lived, eye-catching, upwardly mobile, “sex machine”—almost from scratch!

————————-O————————

Next, sort the students into random pairs. Provide each pair with a copy of the text for a silent reading. This second brief encounter with the text will nudge students to reflect on their own learning moments.

Swallowtail butterflies—ephemeral, flying sex machines!

Photo credit: Howard Cheek/Britannica

Continue by asking students to think in silence for a couple of minute about memorable learning moments they have experienced over the years. The focus can be inside, or in their social and cultural lives outside, of the classroom.

After a few minutes encourage them to talk with their partners about these experiences. Emphasize that they should be selective in what they choose to reveal—respecting privacy and comfort zones. Also reassure students that any subsequent sharing with the entire class will be entirely voluntary.

After a timed six minutes, call the entire class to order and ask if anyone would like to share an interesting learning or Aha! moment. It would be optimal to hear at least half a dozen compelling stories. The following generative questions may (or may not) be necessary as class discourse about the relationship between interpretation, learning and identity unfolds.

To what extent does learning incrementally change who we are?

Do our preconceptions and prejudgements help or hinder the interpretive learning moment?

When can learning shut down?

Reflect on one of your own tension-and-release, “aha,” learning moments where some kind of impasse, or hump, was overcome?

What has been the role of certain teachers, and collaborations with a variety of student peers, in your educational experience thus far?

To what extent do you think that you individually construct your own learning and understanding?

How, if at all, can gaining meta-perspective on your own idiosyncratic learning style enhance your learning?

We do not play things as they are

“The man bent over his guitar,

A shearsman of sorts. The day was green. They said, “You have a blue guitar,

You do not play things as they are.”

The man replied, “Things as they are

Are changed upon the blue guitar.”

And they said then, “But play, you must,

A tune beyond us, yet ourselves,

A tune upon the blue guitar

Of things exactly as they are.””

Turtles all the way down (2024) Oil painting by the author.

“What’s going on?

What’s the deal, man?

What’s happening, brother?

What else is new, my friend?

What’s been shaking up and down the line?”